Features of Erosion

By Alex Jackson

Last updated on

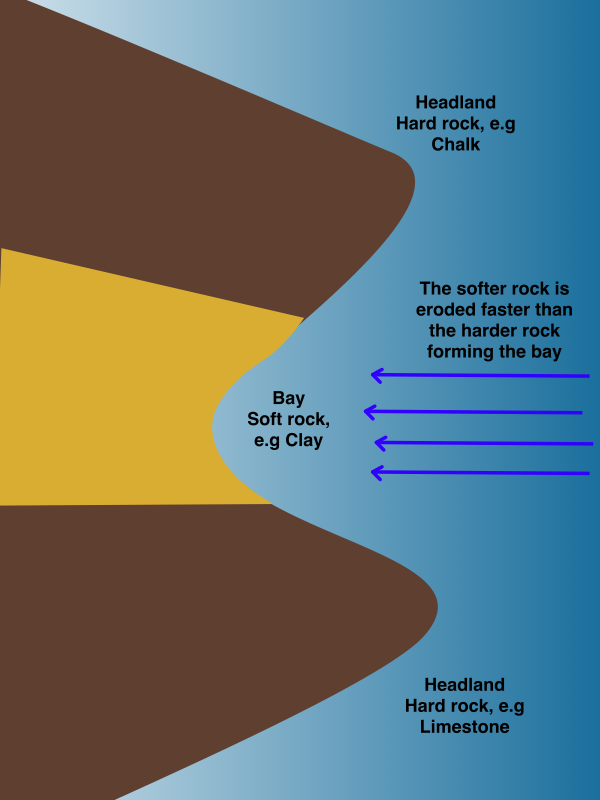

Headlands & Bays (e.g. Swanage Bay)

Headlands and bays, such as Swanage Bay, form on discordant coastlines, where hard and soft rock run in layers at 90˚ to the water. Alternating layers of hard and soft rock allow the sea to erode the soft rock faster, forming a bay but leaving hard rock sticking out, known as a headland. The altering rate of erosion of hard and soft rock is known as differential erosion. As the bay develops, wave refraction around the headlands begins to occur, increasing erosion of the headlands but reducing the erosion and development of the bay due to a loss of wave energy. Headlands and bays can form on concordant coastlines too, as has happened with Lulworth Cove, but this requires the rock to have already been weakened, possibly during an ice age. Irrespective of whether the coastline is concordant or discordant, as wave refraction takes place around the headlands and erosion of the bay is reduced, sub-aerial weathering such as corrosion and corrasion begins to weather the bay, furthering its development.

Wave Cut Notches & Platforms

A wave cut notch is simply a small indent at the base of a cliff formed when a cliff is undercut by the sea. When a wave breaks on a cliff, all of the wave’s energy is concentrated on one specific point and this section of the cliff experiences more rapid erosion via corrasion. This eventually leads to the formation of a wave cut notch, when the cliff has been undercut. As the cliff has been undercut, the section of the cliff above the notch (the overhanging rock) no longer has any support and will, eventually, collapse. The repeated process of the collapse of the cliff and then the undercutting of the cliff is often referred to as the “retreat” of the cliff. As the cliff retreats, a gentle platform (with a gradient less than 5˚), referred to as a wave cut platform, is left behind. This platform is heavily scarred by erosion from the transportation of rock across it. As the platform grows, the waves have to travel further to reach the cliff and they’ll lose more and more of their energy. Once the platform reaches a certain size, the waves will have too little energy by the time they reach the cliff to undercut it and so there is a physical limit on the size a wave cut platform can be.

A wave cut notch on Hilbre Island.

Formation of Caves, Stacks, Stumps, Arches, Blowholes & Geos

Stacks, caves and arches are all iconic features of coastlines. They are also all linked together, along with stumps and arches as they are part of a series of landforms that form as a coast is eroded. Areas on a stretch of coast that have small cracks and joints on them are particularly susceptible to attack from waves, along with bedding planes that lie inline with the direction of the waves. These areas will be eroded very quickly and can be eroded in one of two ways. The first way is simply eroding the crack and causing it to collapse, forming a geo, a steep sided inlet into the side of the coast. Alternatively, the area below the crack or joint is undercut and a small cave will form. If the cave forms on a headland, then on the opposite side of the headland, a second cave can also begin to develop simultaneously. The water erodes the cave via corrosion and hydraulic action, flooding the cave and swilling around it, widening the cave and creating a unique pattern on the surface of the cave. As the two caves are eroded and cut into the headland, they will eventually meet. The resulting, iconic, landform is then referred to as an arch. The roof of the arch has no support however and is highly susceptible to weathering via exfoliation, salt crystallisation and biological weathering. As the weathering continues, the roof of the arch will collapse leaving a stack, a tall, lone piece of land sticking out in the sea. This stack is exposed to the full force of the water and is weathered and eroded heavily. The base of the stack receives a lot of erosion from hydraulic action and corrosion and, eventually, the stack will collapse into the sea leaving behind a small piece of land called a stump.

A blowhole forms in a cave. As a cave moves inland, the roof above it is weakened and as waves crash into the cave, they can be reflected upwards, eroding the roof of the cave. At the same time, weathering on the roof of the cave will help weaken it further and eventually water will be able to break through it, leaving a blowhole.

An arch on Hilbre Island.

An example of a geo on Hilbre Island.

Barton-on-Sea

Barton-on-Sea and its cliffs are located in the south of England, just to the west of the Isle of Wight where it forms a coast with the English Channel. The section of the English Channel which it borders experiences strong winds and has a long fetch, resulting in a fairly fast rate of erosion on the cliffs. The rate of erosion is quickened by the geology of the cliffs, which are mainly composed of salt clay (also known as Barton Clay) and Barton sand in two layers. The combination of the long fetch and weak rocks is resulting in the rapid erosion and mass movement of sections of the cliff which is posing a risk to people and buildings along the stretch of coastline at Barton-on-Sea.

In order to prevent or reduce the risk of a cliff collapse, the local council has carried out several protective measures over the past few decades to try and slow cliff collapse.

December 1993

There was a large cliff slip on the western front of Barton-on-Sea. In response to the collapse, more rock armour was placed by the cliffs to try and reduce the undercutting of them.

September 2001

A collection of sea defences collapsed close to Cliff House. The collapse occurred as a rotational land slide in the Barton Clay formed a bulge in the lower section of the cliffs, which destroyed several drainage pipes.

November 2003

After a period of heavy rainfall, a lot of water had saturated the cliffs and, while no collapse occurred, there was concern that the cliffs could collapse due to the observation of the movement of gravel.

January 2007

Strong winter storms took place over the winter of 2006-2007, with an especially strong storm on the 18th of January. This resulted in the rapid erosion of the beach, where 60% of the sand and shingle was lost. The beaches had acted as a soft engineering technique to protect the cliffs and, as the beaches had been destroyed, a wooden retaining wall (from 1960) had been exposed and damaged which meant that the cliffs were very close to collapse.

In response to the damage, the council constructed a new stone wall using 600 tonnes of boulders to help protect the cliffs and rebuild the beach.

April 2007

After extensive wet weather followed a period of dry weather, concern was again raised regarding the stability of the cliffs. There had been signs of cliff collapse in sections of the cliffs between Cliff House & the Barton-on-Sea shopping area in the form of cracks in the gravel located at the top of the cliff.